About Amaya

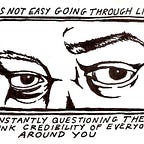

Despite generally considering myself a fairly well informed person, there are a lot of things I don’t pay particularly close attention to. I’m only vaguely aware that the world is running out of sand; I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about concentration camps in Nauru, nor do I frequently find myself tossing and turning over the growing refugee crisis in and around Venezuela. I was a very earnest teenager, always pressing Amnesty International letters into the hands of my uninterested school mates, listening to From Our Own Correspondent with a single minded ardour available only to 14 year olds and the basement-dwelling obsessives; I’m not really like that any more. I got older, got distracted, got disengaged.

The political situation in Nicaragua was, until a few weeks ago, one of the many things I wasn’t paying particular attention to. Nicaragua, I knew, was in central America; the Contras, of Iran-Contra fame, had waged guerrilla war there in the 1980s (against who, though, I’d probably have struggled to remember); and it was where my classmate Amaya was from.

When I was 16, after that dull Irish adolescence of current affairs and bad outfits I alluded to earlier, I somehow wound up at a boarding school in Hong Kong. It was a rather hippy-ish place, and my classmates came from all over the world. I don’t talk about school very much these days, I find- people I’ve known for a long time often have no idea that spent a few years in Hong Kong, not wearing any shoes.

For the two years I was away, my classmates were my family. “We didn’t exactly grow up together”, said Vera Brittain of her friend Winnifred Holtby, “but we grew mature together, which is the next best thing”. I’m not noted for my emotional openness or my naturally effusive demeanour, but I can say without a hint of cynicism that my schoolmates and I loved each other a scary amount. We ate every meal together, shared classes and dorm rooms, travelled together, snuck out together, got drunk together, got in trouble together, and went on strange adventures that are still clear in my mind even half a decade down the line. We had our own language of acronyms and our own social norms, our own occasions and rituals and shrines. We climbed up onto the gym roof and had naked tea parties at midnight, and down into the bowels of the school to caves in the unfilled foundations; we swam in the nearby waterfall, a place halfway up a mountain which we regarded with a quasi-spiritual deference; we went on bad nights out and slept on the roof of the financial services centre in the centre of the city, watching it get grey, smoggy-light in the early morning hours.

School was far from a utopia, but the people made it seem that way more often than they had any right to. The strangely insular nature of the life we all lived there means it’s not something I’ve talked about in the years since, as I went from a year of waitressing on to university in London. I got involved in student politics here in the UK and that became my defining trait, my conversational master key. I became a good student (a development that would undoubtedly shock my school teachers) and as this summer fizzled out I set about packing up my life in London to start a masters’ course in another city. And so I awoke one morning almost a month ago in a room full of boxed up books and bin bags of charity shop bound clothes, ready for another day of boxing up bric-a-brac and determining the ownership of kitchen utensils to look online and see that Amaya, my classmate from Nicaragua, had been abducted by the paramilitary police for her political activities- we’d later find that she’d been charged with terrorism offences, with holding large amounts of weaponry and illegal currency, and taken to a prison notorious for human rights abuses.

Amaya and I weren’t close friends, but two years is a long time to spend as an every-single-day fact of someone else’s life. I sat at my computer, looking at articles about Amaya’s arrest, and thinking about her. I’d shared a bunk bed with her during a very dubious hiking trip in our orientation week- I remembered her peering down at me from the top bunk somewhat suspiciously, big eyes and big hair and (at that point) not very good English. I thought about the all-girls trips we’d make to go skinny dipping in the waterfall, often very early in the morning, splashing about and avoiding water snakes, ecstatically happy to be with each other. A dubious night out clubbing after which Amaya, Campbell and I had retreated to the roof of the financial services centre and shivered until dawn. All the weekends we used to spend at Nicole’s house, sleeping in a big pile together and talking very earnestly and vaguely about how we might change the world. The beach parties we used to have, laughing and dancing, drunk on cheap wine and covered in sand, or trips to Sai Kung on the bus that always seemed to be going a million miles an hour through the trees on the coast road.

One of my overriding memories of Amaya comes from my very last night in school, which I spent in a common room with a slightly disparate group of people, including Bilal, who was bashing away at an acoustic guitar with an incredibly endearing lack of talent, pretence or guile. There wasn’t anything particular to this memory, no grand event- I just remember just watching her and everyone else we knew weave around each other, concluding their lives in a hundred different ways, some big, some small, some obvious, some to this day still mysterious to me.

We all said we were going to change the world, to be idealists, do good. I went through a phase of being very cynical about this, but as I watch the people I lived with get older and do unexpected, sometimes wonderful things, I’ve been getting less cynical. I feel proud to know them all- but, as I tried to decipher newspaper articles in Spanish about the regime and protest movements in Nicaragua, I felt particularly proud to know Amaya. I knew she’d been involved in student movements, in anti-government protests, in things that looked righteous from afar but the gravity of which I’d comprehensively failed to grasp. As I go about my daily business- boiling the kettle, brushing my teeth, walking the streets as I get to know my new city- I keep pausing and thinking of her, still in prison, still facing who knows what. They released a picture of her, hand cuffed and surrounded by balaclava wearing members of the paramilitary police, a massive smile on her face; how can anyone be that brave? That kind of bravery is surely reserved for people I’ve never eaten lunch with, people I’ll never meet. It isn’t, though.

Today she’s in court, while I’m sat at a desk, trying to put together a presentation for a seminar tomorrow. As time goes on I get progressively more afraid for her; I learn more about things in Nicaragua, hear news reports about the government fouling political prisoners’ food, hear from Amaya’s family friends about conditions under Ortega, hear about a porous border between the police and vigilantes, hear about false convictions for murder and arson. I get afraid about what I’m going to hear next, especially today.

My time as a student politicker means that I’m more familiar with Twitter than most of the people I was at school with, and so by means of contribution I’ve found myself running a Twitter account, tweeting out news about Amaya’s case. I’ve started tweeting out pictures of Amaya and the people we were in school with, people from different countries, furiously @ing embassies with photos of smiling teenagers and thinking about a time in my life that I’ve been deliberately leaving off CVs and out of conversations for a long time.

I don’t have my diaries from school with me, so I searched for Amaya’s name in my emails to my parents. There she is, inanely listed as coming to my room for tea, as one of the people I’d eaten brunch with that day, as an attendee at a birthday party, as one of the people whose art I liked, as an altogether usual suspect. The last mention of her is from the very dying days of my final term at school;

“It’s weird, there is so little time left and we all can’t quite realise it. I don’t like to think of how I might never see Amaya (who is going back to medical school in Nicaragua) again. Or at least won’t in a long, long time.”

I hope I see her soon. I hope we all do.